Vidal D’Costa for The Movie Buff: Could you share about your background as a filmmaker, especially what drew you to the field of art and cinema?

Dylan Besseau: Ever since I was a child, I’ve always been drawn to art. I would spend hours sketching my favorite characters in notebooks, and in high school, I even created a little comic book featuring my classmates. At the time, I didn’t really know which path to take, so I enrolled in law school. But I quickly realized it wasn’t something I was passionate about.

After a transitional period working at McDonald’s for two years, I eventually decided to shift towards art studies, where I discovered video editing. My entry into filmmaking happened almost by chance; it wasn’t a path I had planned at all. Everything really started when I met Antoine Godet, with whom I immediately connected, especially through our shared love of Asian cinema, and Guillaume Gevart, whose incredible knowledge of film, like a living encyclopedia, truly inspired me.

“Ever since I was a child, I’ve always been drawn to art” — Dylan Besseau

VD: ‘Makiko’ welcomes viewers into the colourful world of the titular Makiko Furuichi, a Japanese-French artist. I was instantly drawn in by her bubbly and magnetic personality, and of course, the manner in which she speaks on artistic freedoms, her reminiscing about her family history/legacy and what she wishes to achieve through meaningful art. What were your motivations in presenting Makiko’s story to a wider audience, and are there any aspects about her work as an artist that stand out or personally influenced you? Also, do you have a personal favourite work by her?

DB: The creation of “Makiko” came together under rather unusual circumstances. Antoine and I were on the lookout for a story, something raw, something that truly mattered to both of us. At first, we considered François Besse, the former accomplice of Jacques Mesrine. Antoine spoke with him often, but Besse was clear: no more media, no more spotlight. He was now focused on touring prisons across France, sharing his past life as a bandit and raising awareness among inmates. According to him, these moments could not be filmed or shared publicly; they only held their true value in real, face-to-face exchanges. We respected his commitment.

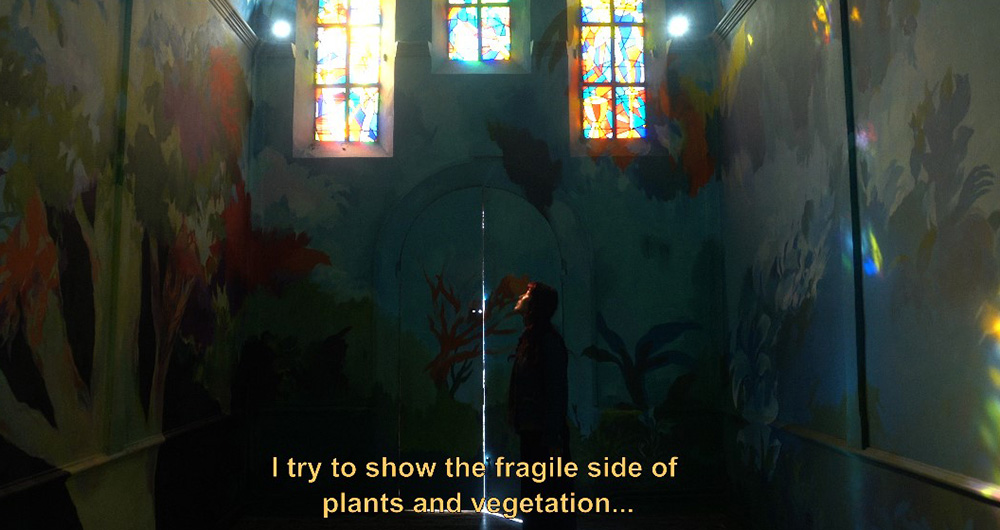

Then one night, coming back from a bar in Nantes, I passed by the opera house. A poster on the street stopped me in my tracks, it mesmerised me. It was a painting by Makiko. At first, I thought she was French. I had no idea she was Japanese. But her work, dreamlike, delicate, left a deep imprint on me. I told Antoine about it. He did some research, discovered her universe, and immediately connected with it. Even her name, Makiko Furuichi, we thought it sounded seriously cool!

Digging a little deeper, we found out that her grandfather, Minokichi Yasui, was one of the first students of the painter Ryusei Kishida. Suddenly, it wasn’t just an art story anymore. There was a lineage, a real journey to tell. Antoine reached out to her, and everything fell into place quite naturally. If I had to choose one work that truly captures her essence, it would be her series of black-and-white drawings. That’s where she goes deeper, beyond the colourful world people often associate her with. She takes a risk, breaks her own codes. And it’s precisely that boldness that makes her so fascinating,

VD: Did Ms. Furuichi offer creative feedback which shaped the narrative or direction of the documentary and that enabled in crafting her story more so through her lens?

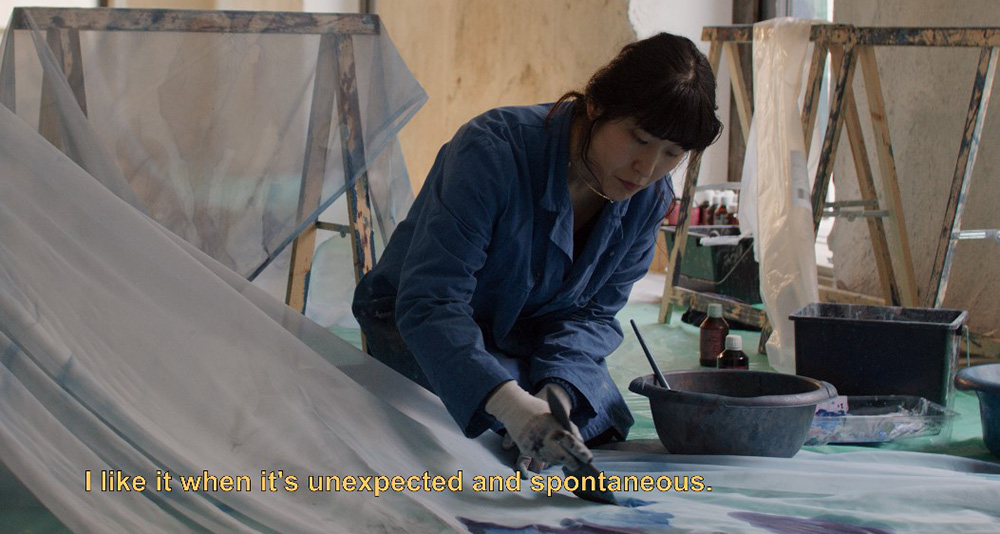

DB: No, Makiko didn’t influence the narration. Everything came together quite spontaneously. Antoine had written a sequence outline, just to have a rough guide for the film. But nothing was really scripted. We chose to capture Makiko in her daily life, without any artifice or staging. What you see in the film is truly her, the way she works, the way she thinks, the way she tells her story.

We wanted to preserve the sincerity of her gestures and her words. When she speaks about her past, we felt it was important to highlight that. Especially because she’s still a young, emerging artist. At first, we thought we’d make a more contemplative, more abstract film. But since she’s not widely known yet, we realised the project needed to first present the person and her work to offer a first glimpse into her world. In the end, the film serves as a foundation, a doorway for people to dive deeper into Makiko’s universe.

VD: You’ve also collaborated with your long-time DP, Antoine Godet, who directs this time. Could you delve into your working relationship with Mr. Godet, and other insights into the brainstorming sessions, creative back-and-forths, etc.?

DB: Yes, Antoine Godet had worked as the director of photography on my previous films. He wanted to move into directing, and for his first project, he asked me to produce it. Since we know each other well, we have a good sense of what suits us artistically. We often share the same film references and cinematic influences. In terms of visuals, Antoine did an impressive job and I really want to acknowledge that. You can clearly see his love for wide shots and the way he composes his frames with a painterly, almost pictorial, intention.

When it came to editing, Antoine initially took a more contemplative approach. The first cut was about an hour and a half long, but the issue was that it didn’t really tell much of a story it was more a sequence of rushes without a strong narrative thread. That’s why I suggested reworking the edit to make it more focused and meaningful for the audience. We even decided to add interviews, even though that’s something we’d like to avoid in the future to keep from leaning too much into an “institutional” style. Of course, the film isn’t perfect, it’s his first and I’m completely understanding of that. But honestly, he has every reason to be proud of what he accomplished.

“Antoine did an impressive job and I really want to acknowledge that..” — Dylan Besseau

VD: I understand that the road to backing a passion project or any creative work is fraught with concerns over financial backing, creative differences, distribution, et al. Did you encounter any such major hurdles, or was it all smooth sailing?

DB: You know, they often say that a project without any problems is usually a bad sign, and honestly, that’s what makes me a bit nervous about “Makiko.” Because, at the end of the day, a producer’s real job is to spend most of their time fixing problems. And on this project… there really weren’t that many. Well, except maybe for one scare a hard drive got corrupted, and we had to spend $900 to recover the footage. But apart from that, the production itself was surprisingly smooth.

We had prepared our gear carefully ahead of time, which helped a lot. For this film, we shot with a Sony A7II, a Red Komodo, and a Panasonic S1H. The total budget was around $40,000, which is pretty low for a 52-minute documentary. So of course, there were some budget constraints. But overall, we’re really happy with how it turned out.

On the music side, we had the chance to work with Lucas Julien Lentz, who had composed for the documentary Copyright Van Gogh. And for the sound mixing and sound design, we collaborated with Luca Boudergui and Benjamin Hoisne from Threefold Sound. The colour grading was handled by Caïque de Souza, and they all did an amazing job. I also want to give a special thanks to those who supported us financially: Arthur Gevart, Guillaume Gevart, Killian Murlock, and Michel Ruchaud. Without them, this project wouldn’t have been possible. And a big thank you to Yuichi Yokoyama, who kindly agreed to take part in the film, even though he almost always refuses to appear on camera.

VD: Lastly, what are some other works in the pipeline that our readers can look forward to from you, either as a director or as a producer?

DB: As a director, I’m currently working on “Blast Punch,” a documentary about street fighting. But the project is on hold for now, one of the main antagonists in the film has recently gone back to prison. In the meantime, I’m taking the opportunity to continue filming another documentary, this time about a dentist who dreams of opening his own restaurant. At the same time, with my friend Guillaume Gevart, we’re restoring films by Shin Sang-Ok. Some of these films have never been released, they’re not even listed in any online databases. That makes them truly unique pieces of cinema history.

We at The Movie Buff wish the team behind “Makiko” the very best going forward. The film is scheduled for a 2026 release and will premiere on the festival circuit. Follow us for updates.